Earlier in this blog I wrote The art of repair: responding to the Neues Museum, about a museum in Berlin which has been painstakingly repaired so that the original bomb-damaged building and new repairs are distinct yet harmonious. Looking at frescoes in Italy over the past few weeks and the various ways in which they have been conserved or restored, has prompted me to return to the theme of repair. A theme which is relevant to my works on canvas, in which I resew their threads, using the act of repair to make something new. And now, in the aftermath of Christmas, seems as appropriate a time as any to post pictures of religious paintings, which dominated my Italian trip.

I have been fascinated by the diversity of ways in which frescoes have been repaired and individual conservators have sought to preserve the original authenticity of the work, while presenting as complete an image as possible for visitors to enjoy. Of course, there are many, many frescoes where the repair is so complete that it is indistinguishable from the original. And those frescoes which have been recently conserved so that new and old are distinct, are more than likely to have had older repairs which were done with less transparency. As with any painting of a certain age, it is hard to know whether what one sees now is as the original artist intended it five hundred and more years ago.

For me, the different fresco repairs which I came across seemed to split into acts of stabilization or conservation, and acts of recreation or restoration. In the first, which I came across a lot, the original is preserved but there is minimal attempt to recreate parts of the missing image. I saw only one clear example of the second, in which the restored fresco presented a complete image but on close inspection, one could see where additions have been made.

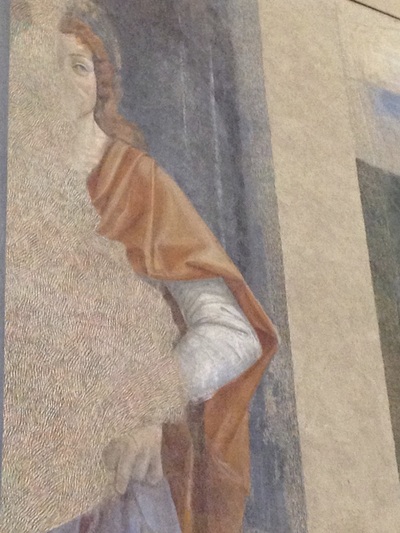

This small Madonna and Child, in the house where Raphael was born and lived as a child, is claimed to be one of Raphael’s earliest works, painted under the supervision of his father, Giovanni Santi, who died when Raphael was eleven. Alternatively it has been attributed to his father, and interpreted as showing the newly born Raphael in the arms of his mother. Regardless of the original painter, parts of the Madonna or mother’s blue gown on her right shoulder and arm have been restored. The short fine, linear brush strokes that create the repair are different from the planes of colour, delicately blended together, in the remainder of the fresco. This is a work in a domestic setting, which meant that I could get close to it and see the different painting styles. Other frescoes in grander settings, the Sistine Chapel being the most obvious that comes to my mind, where one is kept at a distance are also repaired in this way. But one does not get close enough for the optical illusion to start to breakdown in the way it did here for me, my eye oscillating between the whole picture and the differences in painting style.

I have been fascinated by the diversity of ways in which frescoes have been repaired and individual conservators have sought to preserve the original authenticity of the work, while presenting as complete an image as possible for visitors to enjoy. Of course, there are many, many frescoes where the repair is so complete that it is indistinguishable from the original. And those frescoes which have been recently conserved so that new and old are distinct, are more than likely to have had older repairs which were done with less transparency. As with any painting of a certain age, it is hard to know whether what one sees now is as the original artist intended it five hundred and more years ago.

For me, the different fresco repairs which I came across seemed to split into acts of stabilization or conservation, and acts of recreation or restoration. In the first, which I came across a lot, the original is preserved but there is minimal attempt to recreate parts of the missing image. I saw only one clear example of the second, in which the restored fresco presented a complete image but on close inspection, one could see where additions have been made.

This small Madonna and Child, in the house where Raphael was born and lived as a child, is claimed to be one of Raphael’s earliest works, painted under the supervision of his father, Giovanni Santi, who died when Raphael was eleven. Alternatively it has been attributed to his father, and interpreted as showing the newly born Raphael in the arms of his mother. Regardless of the original painter, parts of the Madonna or mother’s blue gown on her right shoulder and arm have been restored. The short fine, linear brush strokes that create the repair are different from the planes of colour, delicately blended together, in the remainder of the fresco. This is a work in a domestic setting, which meant that I could get close to it and see the different painting styles. Other frescoes in grander settings, the Sistine Chapel being the most obvious that comes to my mind, where one is kept at a distance are also repaired in this way. But one does not get close enough for the optical illusion to start to breakdown in the way it did here for me, my eye oscillating between the whole picture and the differences in painting style.

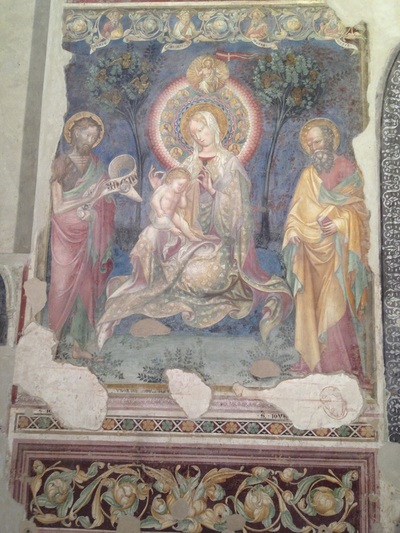

Much easier to discern are the disruptions left in images when no attempt at restoration has been made. So, in Santa Croce in Florence, the face of a figure in a crowd has been left as blank plaster, its shape forming a silhouette of forehead, nose and beard, between a faded frescoed red cap and cloak, painted by Giotto. While, multi-coloured cross-hatching cuts across the face and body of a figure at the edge of Domenica Ghirlandio’s Madonna della Misericordia e la Pietà in Ognisanti in the same city. There has been no attempt to blend with the colours of the skin, hair and clothes which remain. Rather than complete the picture, the newly-painted addition sits as an amorphous, abstract shape contrasting with the modeled eye, shoulder and hand of the original, drawing attention to the skilled way in which they have been painted. Finally, below the foot of St John the Evangelist a drawn head from an earlier image has been revealed through the fragmenting of the image which sits on top. It disrupts the decorative border of the fresco in the Oratorio di San Giovanni Battista in Urbino.

I am drawn to these disruptions and unexpected disturbances. For me, they make the history of the images more transparent and have more integrity than restorations in which the original is re-rendered as complete. Through their modern interventions they clearly demarcate old and new, bringing authenticity to what remains of the former. I also like the unexpectedness of the resulting whole image, original and repair jostling for attention.

Of course, the images I have shown just have small fragments missing from a larger scene which is still largely visible and decipherable. I saw older frescoes in Pompeii and Herculaneum, used to decorate the interior of houses, which were far more damaged. Criss-crossed with cracks and patches of plaster, I couldn’t picture the whole decorative effect but the fresco fragments which remained were enough: snatches of bright colours, intricate detail and trompe l’oeil illusion. In some rooms, the design had been continued beyond the fragments, scratched into fresh plaster, to give an idea of the complete composition.

Of course, the images I have shown just have small fragments missing from a larger scene which is still largely visible and decipherable. I saw older frescoes in Pompeii and Herculaneum, used to decorate the interior of houses, which were far more damaged. Criss-crossed with cracks and patches of plaster, I couldn’t picture the whole decorative effect but the fresco fragments which remained were enough: snatches of bright colours, intricate detail and trompe l’oeil illusion. In some rooms, the design had been continued beyond the fragments, scratched into fresh plaster, to give an idea of the complete composition.

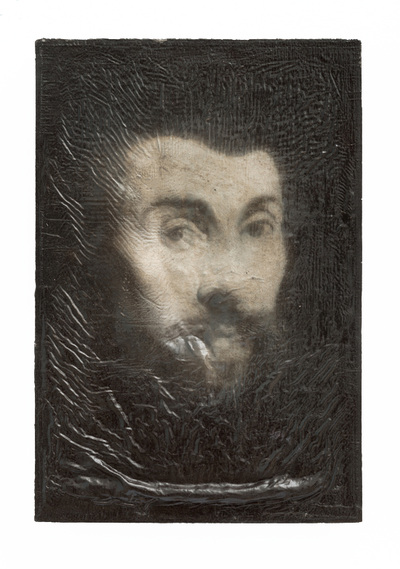

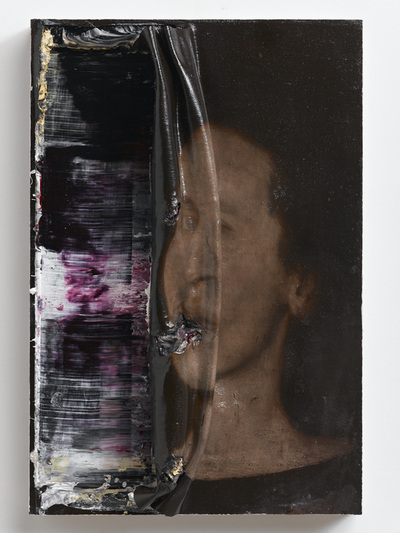

In my earlier blog post I wrote that my experience of the Neues Museum brought “me back to the possibility that I need to use materials with a richer narrative than new raw canvas”. At the time I did not know what those materials should be. I am currently working on a canvas in which I have unpicked my own painting, so that traces of the original painting remain but are abstracted by the act of unpicking and resewing. For me this creates a richer narrative than the blank canvas I had previously used and also the painted images before they are disrupted, acting in a similar way to the conserved rather than restored frescoes.

A slightly longer version of this post was first published in my Reside Residency blog.

A slightly longer version of this post was first published in my Reside Residency blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed