After years of making stark, minimalist work I have become an unashamed romantic. So I have spent time these past few months looking at the work of Caspar David Friedrich, taking advantage of the fact that so many of his paintings are here in Germany. I have been to Greifswald, a small town on the Baltic coast to see where he was born, and I have travelled to Dresden where he lived for most of his life. I have attempted to read – in German - about his life and his work. My practice is very different to his on many fundamental levels: in its appearance, method and motivation. Yet there are, I feel, similarities of intent and, more importantly, things that I would like to learn from his paintings to enrich what I do.

His work is easily identifiable, as popular images used to represent the Romantic era. But my observation, as I have sat in museums and sketched or written, is that people don’t spend very long looking at them once they have linked image and artist. This may be because many people don’t actually spend very long looking at any art, but perhaps it is also because his paintings are too earnest and sentimental for our contemporary eyes, the colours, particularly of sunrise and sunset, now too clichéd and cloying. Looking past the vivid orange sky and contrasting lilac mountains I have found these seemingly straightforward paintings are created from complex compositions and unusual perspectives which hide as much as they reveal.

His work is easily identifiable, as popular images used to represent the Romantic era. But my observation, as I have sat in museums and sketched or written, is that people don’t spend very long looking at them once they have linked image and artist. This may be because many people don’t actually spend very long looking at any art, but perhaps it is also because his paintings are too earnest and sentimental for our contemporary eyes, the colours, particularly of sunrise and sunset, now too clichéd and cloying. Looking past the vivid orange sky and contrasting lilac mountains I have found these seemingly straightforward paintings are created from complex compositions and unusual perspectives which hide as much as they reveal.

Going to Greifswald was surprising. I was expecting a grand landscape to have inspired the painter to his life’s work (although he did some interior and street scenes the majority of his paintings are land and seascapes). Instead it was a pretty mix of fields and ditches interspersed with small copses and villages; in other words, nothing spectacular. My train ride home was accompanied by a Friedrich-esque sunset, below, which brought some of the motifs he used to life and asserted the dominance of the sky. In this we share a similar influence, as I grew up near the Cambridgeshire Fens where the land is flat and the skies wide open. I am drawn to similar open views and since 2011 have been drawing them, repeating landscape forms until the image becomes abstracted.

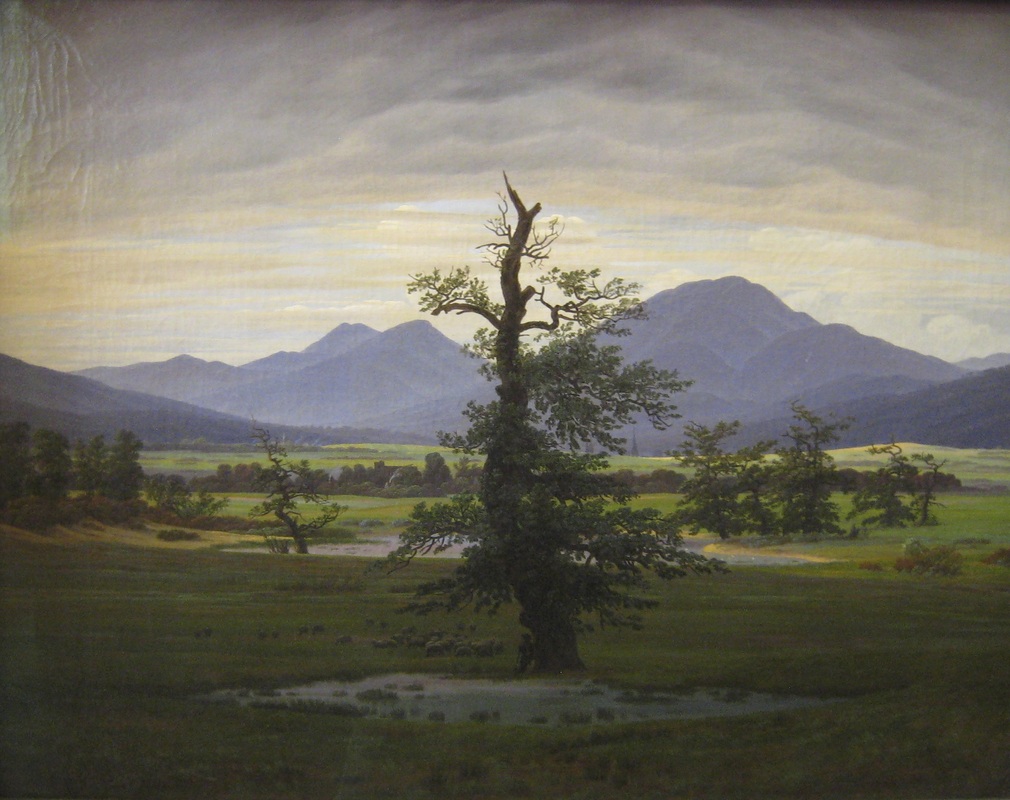

For Friedrich, as for other Romantics of his era, the beauty of nature represented the power and benevolence of God. There is a real tenderness in his paintings that evokes this sentiment and which I feel comes from his focus on detail throughout the image - lovingly recreating each leaf on a tree as in Gartenterrasse at the Neuer Pavillion in Berlin or branch on a tree as in Gebüsch im Schnee(probably my favourite of all the Friedrich paintings I have seen, for its very simple subject matter) in the Albertinum in Dresden - and a sense that they have been produced under quiet contemplation. While I do not see nature in this way I can still appreciate the awe of nature, the power of God having been replaced in my eyes by the wonder of the forces of evolution and erosion. In choosing to draw landscapes, from the detail of weeds to distant views of mountains, I am also retreating from the encroaching urbanisation of contemporary life in much the same way that the Romantics turned their backs on the first signs of the industrial revolution infiltrating into nature. Look carefully at a Friedrich landscape and you will see signs of life - figures in the shade of trees as in Der einsame Baum, below, houses clinging to the hillside – but these people do not belong to the giddy rush of civilising progress that was happening at the time.

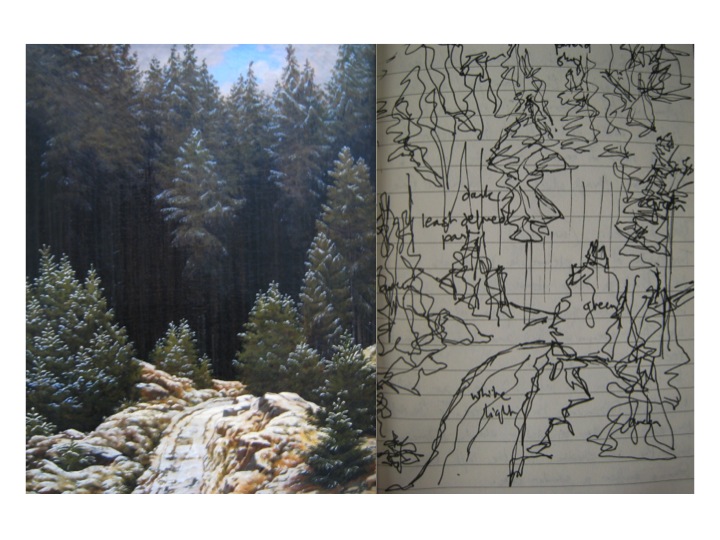

Friedrich believed that a painter should paint not only what they see in front of them but what they feel within, and if they feel nothing then they shouldn’t paint at all[1]. He sketched a lot in the open and then waited until a composition came to him, collaged together from his observations of nature, before putting it down on canvas, methodically in his studio. Das brennende Neubrandenburg, below, shows the clear, confident ink drawing to which Friedrich started adding glazes of oil paint but never finished. The atmospheric effects in his work may have come from memory, or an oil sketch of clouds attributed to him in the Pommersches Landesmusuem implies he also captured weather effects to use later. While I draw from nature, I work very differently, allowing an image to evolve from sketches I make from nature, not always knowing what the next step will be and never having a final composition in mind. However, I am drawn to the idea of collaging together sketches to form an ideal landscape and can imagine that this would be a good strategy for creating, now as I travel and also when I return to juggling art and paid work. I would like these sketches to invoke some of the tender detail of Friedrich’s work.

The thing that draws me to seek out Friedrich’s paintings again and again, and above other landscape painters, is the drama and inventiveness of their composition. They seem so simple, but from attempting to sketch them I now know what I must have instinctively perceived, their skillful complexity.

I feel that they really play with me, as a viewer. In some cases frustrating my view, hiding as much as they reveal. Rocks rise up in the centre of the picture, as in Das Kreuz im Gebirge, The effects of light or weather are employed to obscure the view. The landscapes of Ziehende Wolken, above, and Nebel im Elbtal are partially shrouded in mist, with the viewer receiving only fleeting glimpses of the valley below in the latter painting. In some pictures the foreground is cast into gloom making it difficult to discern any detail. With this latter obstructing effect, however, I am unclear whether Friedrich intended it to act as strongly as it does or whether it is the combined effect of the museum lighting, glazing and darkening varnish on the works.

The composition directs the way in which we navigate through the elements of the painting. A path or river directing the way in which we move from fore to mid to background. Strong vertical, horizontal or diagonals attracting our attention at the expense of small details such as the shepherd tending his flock in Der einsame Baum, as I mentioned before (above), or a sailing boat about to ground itself in the shallow river in Das Grosse Gehege bei Dresden. These details only revealed themselves to me as I stopped and really contemplated the pictures.

Friedrich also used changes in perspective to direct attention to particular elements of the composition. In some cases the picture is uniformly detailed, performing a feat the eye cannot manage, of presenting the background to the same level of detail as the foreground, flattening away pictorial illusion. A picture such as Eichbaum im Schnee, below, focuses on a single tree, obscuring anything but the foreground. While the composition and detail of Wiesen bei Greifswald focuses on the background of the town of Greifswald, with the foreground of bushes and mid-ground of horses and geese in a meadow, seemingly incidental, decorative elements for the main image. Copses or rock formations serve as formal markers between fore, mid and background, setting the scene out as though in a theatre-set stage.

The composition directs the way in which we navigate through the elements of the painting. A path or river directing the way in which we move from fore to mid to background. Strong vertical, horizontal or diagonals attracting our attention at the expense of small details such as the shepherd tending his flock in Der einsame Baum, as I mentioned before (above), or a sailing boat about to ground itself in the shallow river in Das Grosse Gehege bei Dresden. These details only revealed themselves to me as I stopped and really contemplated the pictures.

Friedrich also used changes in perspective to direct attention to particular elements of the composition. In some cases the picture is uniformly detailed, performing a feat the eye cannot manage, of presenting the background to the same level of detail as the foreground, flattening away pictorial illusion. A picture such as Eichbaum im Schnee, below, focuses on a single tree, obscuring anything but the foreground. While the composition and detail of Wiesen bei Greifswald focuses on the background of the town of Greifswald, with the foreground of bushes and mid-ground of horses and geese in a meadow, seemingly incidental, decorative elements for the main image. Copses or rock formations serve as formal markers between fore, mid and background, setting the scene out as though in a theatre-set stage.

I mentioned at the start of this post that romantic influences have crept into my own work recently. I hope that you can see from previous posts that both my subject matter of recent months, landscape and particularly, weeds, and the heightened colouring I use reference the romantic. I would also like to learn from Friedrich’s compositions. I have no doubt that he carefully thought through the complexity of his paintings, either as he constructed them in his mind or as he put them down on canvas. I don’t want to directly reference his work and I will have to achieve this in a different way as I work more directly. I plan to directly collage together different sketches to create a complex composition and play with perspective. The act of looking at Friedrich’s paintings, sketching from them and now writing about them has been very useful in giving me ideas as to how to add complexity to my work. I will know when I have mastered this when I can also make my work appear as deceptively simple as his paintings do.

[1] The Abstract Sublime, Robert Rosenblum, Arts News, February 1961

This post was first published on my Reside Residency blog

[1] The Abstract Sublime, Robert Rosenblum, Arts News, February 1961

This post was first published on my Reside Residency blog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed