This post serves, I hope, as a good bridge between my time in Berlin and the next few weeks that I will spend in Italy. I am writing it in Bologna about an Italian artist, Nicola Samorì, who studied here and whose work I saw the day before I left Berlin. His show, Guarigione Dell’Ossesso at Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, was described to me as perfect baroque-style paintings that the artist then destroys so it naturally piqued my interest.

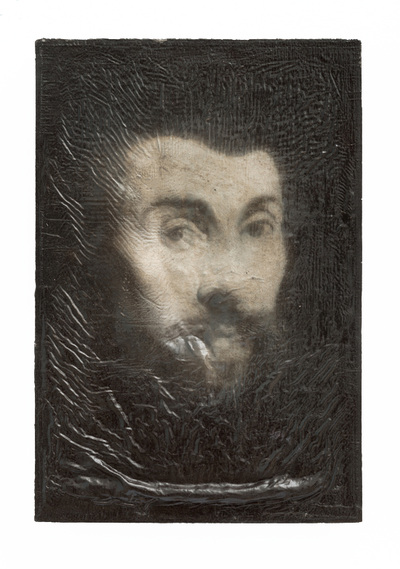

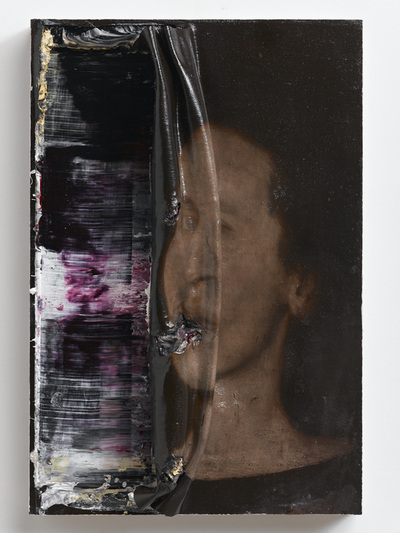

And what destruction! The paintings are gouged, pierced, flecked, scratched, scrunched, shrouded and pummeled. The act of their destruction being all the more perverse because it is carried out on paintings which have been carefully rendered with art historical references and technique. I imagine the artist labouriously painting for weeks or maybe months, building up layer upon layer of paint, and then one day turning around and destroying these creations in which he has invested so much. The gallery’s press release states that Samorì examines obsession, one aspect of which is the obsession of the artist with his own work. Yet he is neither an artist who is precious about his paintings, nor a Victor Frankenstein, who seeks to destroy because he is horrified by what he has created. Far from it, he then puts his destroyed masterpieces on display. His paintings both refer to the past through their subject matter and the manner in which they are depicted, and are rooted in the contemporary, by their very recent act of destruction.

I was first drawn to Vomere, a copper-surfaced diptych, peppered by oval forms, the heads of an audience who are looking at a painted figure forming a table in front of them. This life-size figure is in the process of being physically dissected, a process we may have interrupted. The skin of paint has been half pushed and pulled away, echoing the fragile surface covering our bodies. But rather than revealing bones, muscles and tendons, we see a black and blank undersurface. Pulling the surface away hides rather than enlightens and we, like the unseen copper-covered faces of the curious in the diptych, are left un-seeing.

And what destruction! The paintings are gouged, pierced, flecked, scratched, scrunched, shrouded and pummeled. The act of their destruction being all the more perverse because it is carried out on paintings which have been carefully rendered with art historical references and technique. I imagine the artist labouriously painting for weeks or maybe months, building up layer upon layer of paint, and then one day turning around and destroying these creations in which he has invested so much. The gallery’s press release states that Samorì examines obsession, one aspect of which is the obsession of the artist with his own work. Yet he is neither an artist who is precious about his paintings, nor a Victor Frankenstein, who seeks to destroy because he is horrified by what he has created. Far from it, he then puts his destroyed masterpieces on display. His paintings both refer to the past through their subject matter and the manner in which they are depicted, and are rooted in the contemporary, by their very recent act of destruction.

I was first drawn to Vomere, a copper-surfaced diptych, peppered by oval forms, the heads of an audience who are looking at a painted figure forming a table in front of them. This life-size figure is in the process of being physically dissected, a process we may have interrupted. The skin of paint has been half pushed and pulled away, echoing the fragile surface covering our bodies. But rather than revealing bones, muscles and tendons, we see a black and blank undersurface. Pulling the surface away hides rather than enlightens and we, like the unseen copper-covered faces of the curious in the diptych, are left un-seeing.

Sotto gli occhi la forma stanca, 2013, repeats the act of dissection, scrunching up the surface of a Christ-like portrait. Displayed horizontally we look down upon to it, as though in a coffin, invoking pity for the recent fate it has suffered at the hands of the artist. If google is right, the title translates into English as ‘under the eyes of the tired form’ suggesting a rebellious compulsion from the artist rather than a desire to revere the tradition and history in which he works. For me this painting makes reference to formal qualities, to the deception of real life that paintings seek to invoke, when in reality they are pigment, medium and supporting surface. In the past, paintings were commissioned to invoke devotion, loyalty and awe. Something which they achieved more or less successfully through their ability to deceive, allowing the viewer to forget the reality of what was before their eyes. And so Samorì’s destruction is like a magician revealing his tricks, destroying the illusion.

A group of four small portraits seem to me to reveal a different intent in their destruction. These faces sit on surfaces of paint inches thick, built up over time, then distorted by gouging, scrunching or shriveled from the weight of drying oil paint. Those surfaces where the paint has been infiltrated reveal bright colours which do not feature on the austere restrained final portraits. Where do these colours come from? Were the portraits painted in a lighter style; beneath the surface do they show the sitter in different times, styles or a completely different image? In this the traces that are shown are like the compositional changes which X-rays of masterpieces expose, changes which those artists wanted to hide but which Samorì hints at. It is as though the paintings have started to reveal the history of either their sitter, beneath their formal pose, or of their making. Samorì’s exhibition title translates as ‘healing the obsessed’ but these paintings generated more obsession for me through the intrigue the under-layers create in my mind, the potential histories which lie beneath the surface.

I wonder what constitutes a good act of destruction for Samorì? The act of destruction that he carries out is full of conviction. They feel like singular actions: actions that cannot be repeated or remediated, although they may be pondered and plotted by the artist long before they are carried out. At art school I remember a tutor telling me that the artist Angela De La Cruz, who similarly disrupts her paintings, at times felt she had gone too far and she would then try to bring her paintings back from the brink of destruction. In her case this may be easier as she focuses on destroying the support for her paintings, which reference minimalist and colour-field painting, the canvas stretcher. Maybe Samorì’s destruction is closer to the tense balance that Alexis Harding seeks to create in his paintings where colour and form slide, sometimes hanging precariously from the support but never quite slipping off.

It may seem strange to link these painters together as their work references very different eras and, so, outwardly appears entirely distinct. However, I think they have commonalities in their underlying intent, and in the use of destruction as part of their creative process. By grounding his work in a more distant art historical past, Samorì displays a technical virtuoso that the other artists do not. For me, this adds a rich drama to his work and makes the final act of destruction all the more powerful.

Guarigione Dell’Ossesso by Nicola Samorì was at Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin, from 25 October to 7 December. With thanks to the gallery for providing me with photographs from the exhibition to use in this blog.

This post was first published in my Reside Residency blog.

It may seem strange to link these painters together as their work references very different eras and, so, outwardly appears entirely distinct. However, I think they have commonalities in their underlying intent, and in the use of destruction as part of their creative process. By grounding his work in a more distant art historical past, Samorì displays a technical virtuoso that the other artists do not. For me, this adds a rich drama to his work and makes the final act of destruction all the more powerful.

Guarigione Dell’Ossesso by Nicola Samorì was at Galerie Christian Ehrentraut, Berlin, from 25 October to 7 December. With thanks to the gallery for providing me with photographs from the exhibition to use in this blog.

This post was first published in my Reside Residency blog.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed